This month I want to talk about some of the amazing prizes that we have for the 2022 Gunmaker’s Hall Giveaway. Jeff Luke has been making some of the finest hunting pouches you can find. He is a stickler for historically accurate work. He gave me a description of the pouch he made for us in a recent conversation. Jeff explained it like this.

2022 Gunmaker's Hall Giveaway

FREE FOR AGES 12-15 - POWDERHORN & HUNTING POUCH CLASS

Final days to get signed up for the chance to take this class!

Thanks to Crazy Crow Trading Post for donating the horns for the kids!

FREE FOR AGES 12-15

POWDERHORN & HUNTING POUCH CLASS

SATURDAY, JUNE 18, 2022, FROM 8:00- 5:00

Free to 10 students (ages 12-15) selected from a lottery of applicants. Pizza lunch will be provided. Each student will make a powderhorn and hunting pouch like the set below.

To apply for the drawing fill in the information at the following page link https://www.nmlra.org/classes-1 or call the NMLRA office at 812-667-5131. For more information or questions contact Amber at the NMLRA office at 812-667-5131 or amay@nmlra.org.

Drawing will be held on June 1, 2022 and 10 lucky students will be notified.

Fixin' Up Buffler | Recipies for Cooking Buffalo by John Curry

This article first appeared in the February 2021 Issue of Muzzle Blasts Magazine. Join the NMLRA today to recieve Muzzle Blasts Magazine, the only monthly muzzleloading magazine.

So many old narratives tend to suggest, probably nothing quite so commonly eaten along the far-western, 18th century frontier as buffalo. These great, shaggy beasts roamed throughout the valleys of the Ohio, Green, Tennessee and Cumberland River drainages in massive, seemingly numberless heards. In speaking of his father's early exploits into Kentucky, Nathan Boone writes: "He discovered several of the noted salt licks or springs, which in every case were easily found by following the well-beaten buf-falo roads leading to them. He visited the Upper and Lower Blue Licks on the Licking River. At the latter place he saw thousands of buffaloes..."1 Think of it... Thousands! Like out on the Great Plains a century later. Fortunately enough for us, they made huge, fairly easy targets with hundreds of pounds of red meat that tasted like the best steak you ever ate in your life.

When it came to buffalo hunting, pretty much everybody got into the act! On a danger-filled journey from Fort Harrod to Louisville, the famous far-western backwoodsman Daniel Trabue relates: "We went to Harrodsburgh, stayd all night. In the morning, Col. Harrod and his Lady, Colonel McGary, and several other Jentlemen and ladys started - about 20 Men and about 6 Ladys. When we had Got a bout one Mile from the Fort I Descovered lndeans in the woods and running to Get before us. I told McGary of it. He halted the company and he went to see the sighn. He came back, said he saw the indeans, and said we was not able to fight them while we had these women. And we retreated to the Fort. A party of men went from the fort and found the indeans had gone away. The next morning we set out again. We had about 15 men and 3 ladies on our next rout. Mistress Harrod Killed a Buffeloe as an exploit on the rout." 2 Fancy that! Even Jim Harrod's petite, little wife was a shootin' buffalo!

Now reliable documentation as well as countless, first per-son narratives show deer and turkey - just as popular, with black bear, not quite so much but nonetheless a heartily accepted staple. Have to admit, I've eaten my share of venison and wild turkey. I'm also very fond of bear meat. All the same; for my two cents worth - you just can't beat buffler. And everybody seemed to be hunting it. So... as a suitable ending for last month's article, I figure I'd just pass along a few buffalo recipes.

Here at Fort Harrod, anytime our little group of Historic interpreters are doing anything or every now and then, anytime we have a fairly large group of reenacters drop by, we always look forward to Mary Barlow's tremendous, buffalo chili. It's really good, easy to make... and here's how she does it:

Miz Mary Barlow’s Buffalo Chili

Brown 1 lb. ground buffalo beef.

Stir in (your choice) chili seasonings mix .

Add one can (14.5 oz.) diced tomatoes, undrained.

Add one can (16 oz.) kidney beans, undrained.

Bring to a boil, cover and simmer for 10 minutes.

Now if you want everybody's eyes to roll back in their heads and slap themselves silly with their own tongues, try this next one on for size. Juniper berries were very com-mon in the bluegrass of Kentucky (still are) so it would have been a tasty and interesting twist on your buffler. The onions and sweet potatoes would be procured after the first gardens were set in. I don't know about the lick salt. It does have its own flavor but it's not that easy to get. Check the dealers and traders in Muzzle Blasts.

Buffalo Steak with Caramelized Onions and Pan Fried Sweet Potatoes

4 bone-in, buffalo strip steaks

10 dried juniper berries plus oil of your choice for rubbing

Lick salt (if you can get it), if not regular salt will do

1 to 2 tablespoons of peanut oil for pan-frying

Freshly ground pepper

Grind juniper berries with the salt and pepper using a mortar and pestle or the like. Rub mixture and a bit of oil in just before cooking. Heat the oil in a heavy pan until it's very hot- almost smoking. Sear the steaks for 3 min-utes on each side over high heat before turning down the burner. Cook over moderate heat for an additional 8 to 12 minutes, turning the steaks every few minutes as they slowly brown. Check for doneness often. Rest the steaks (covered) in a warm place for 5 minutes. Pile caramelized onions on top of each steak and surround with pan-fried sweet potatoes.

You can't hardly make a stew I don't like. And this Conestoga Stew doesn't necessarily have to be buffalo either. Any kind of meat would have been used: buf-falo, deer, elk, turkey, small game... You name it and guess what? Its stew! Buffalo however was so darned easy to procure. Upon coming toward a fine salt lick he discovered in the summer of 1770 and later naming both a near-by creek and the lick after himself, Isaac Bledsoe says: "..he experienced some difficulty in riding along the path, so crowded was it and on either side with buffalo; and when he reached the bank of the creek at the lick, he found the entire flat surrounding the lick of about one hundred acres covered with a moving mass of buffalo, which he not only estimated by hundreds but thou-sands." 3 My, my! Once again, buffer just all over the place. Put a little something with it (as in this next recipe) and you've got a meal fit for a king.

Conestoga Buffalo Stew

3 pounds boneless buffalo stew meat Salt and pepper 1 large onion, sliced

4 medium potatoes, cut into chunks

8 medium carrots, cut into chunks

2 tablespoons flour

Plain and simple: Cut buffalo into serving-sized portions and place in a heavy pot. Season with salt and pepper. Add onion and enough water to cover the bottom of pot. Cook, covered, over medium heat. When meat is cooking well, remove the lid and allow the meat to cook in its juices. Turn the meat with a fork until brown. Add potatoes and carrots. Cover and cook over low heat for about 1 hour. Check frequent-ly; if juices are cooking out, add water. When meat is fork tender, add the flour to water and then pour over the meat. Stir well. If broth becomes too thick, add more water. Simmer until ready to serve.

Anne McGinty was quite a gal, a real pioneer in the true sense of the word and much revered by the little settlement of Harrodstown. In the late 1770's/early 1780's she owned and ran an "Ordinary" on the southeast side of old Fort Harrod. Sold alcohol, food, livery service and over-night lodging to weary, Kentucky frontier travelers. Received her license (and some stern advice} straight from the Governor of Virginia, Patrick Henry himself. Once again, buffalo wasn't the only sort of meat a lad might run across in one of Anne's meat pies. Anything from squirrel on up would literally be "fair game".

Anne McGinty’s Fried Meat Pies

1 lb. ground buffalo

1 tsp. smoked paprika

½ tsp. ground cumin

½ tsp. dried oregano

2 cups corn or white hominy

1/3 cup diced green peppers

1/3 cup grated carrot

1/3 cup chopped yellow onion

1/3 cup chopped green onion

2 tsp. minced garlic

1 T Worcestershire sauce

2 or 3 T all-purpose flour

Salt & pepper to taste.

Brown meat over medium heat in a large cast iron skillet. Add paprika, cumin, salt, pepper and oregano. Mix well. Reduce heat to medium-low and let simmer for about

3 minutes to blend the flavors. Stir in the corn/hominy, green peppers, carrot, yellow onion, green onions and garlic. Reduce heat to low, cover and simmer, stirring occa-sionally for about 5 minutes or until vegetables are tender. Remove from heat and stir in the Worcestershire sauce. Add in just enough flour to absorb the grease. Spoon about 2 heaping tablespoons onto each dough circle. Fold over and crimp the edges with your fingers or a fork. In a medium saucepan, heat 2 to 3 inches of oil over medi-um-high heat to about 350°F. Fry pies in the oil a few at a time until golden brown, about 2 minutes per side. Serve warm.

It's exceeding hard to imagine how many buffalo roamed through the entire length and breadth of Kentucky's majestic, Green River basin. Well before the era of the longhunter, the French and their Native friends called it the "Buffalo River". My last month's article roughly cen-tered around a number of historic, Green River hunts and scouts I've done myself and a handful I've read about over the years... drawing most especially from Daniel Trabue's crucially important, buffalo hunt made during the hard winter of 1779-1780. Traveling to Bullitt's Lick for salt by way of Logan's Station and Ft. Harrod, Trabue tells us: "It was suppriseing to see the quantity of people that had recently moved out to Kentucky and they weare more yet a coming. Mr. Smith, Mr. Foster, and these same young men, and several others, and myself started for the woods. Took some of our salt and 2 Negro Men with axxes to cut wood, for the hard winter had began. The snow was Deep and the weather cold. We went to Green River and soon killed some Good fat Buffeloos. Mr. Foster and some others took their loads and went to the fort. The weather at last got so intencly cold that we had to lye by for several days. The snow was fully knee deep. Our meet that we had kept for our own eating failed. The Turkeys had got poore."

The weather had altered a little for the better. Mr. Smith and I concluded we would go out and try our luck once more as we had nothing to eat. We made socks to go over our shews with Buffelo skins putting the wool inside and we had woolen gloves . We put on 2 pair of gloves and Buffeloe socks on over our shews. We had not got fair before we found 11 buffeloes in one Gang. Shot down one. They broak and run off We boath shot at once and killed 2 more. The Dogs run off after them, stopt them again. We concluded to shoot the leaders - to wit, the Old cows - and then the younger ones would not leave them... Made up a good worm fire and guted all our buffeloes before we went to sleep." 4 I'll bet those hungry hunters ate their fill of buffalo that evening too! Donchathink? The following I believe, is a slightly fancied up, 21st century example of what might have been on the menu that night.

Green River Buffalo Roast

1 3 - 4 pound roast

1 tablespoon salt

1 tsp. pepper

½ tsp. garlic powder

2 tablespoons of rub (your choice)

2 cups of water

Preheat oven to 350°. Sprinkle roast with the salt, pepper and garlic powder. Work the rub in all over the roast. Place in a roaster with the water. Seal the top with foil. Bake on bottom rack of oven for 1 ½ hours, or until tender. Use the drippings for gravy. Serves 8 to 10.

Can't deny I have a sincere partiality for buffalo meat. Always have. I've never been able to understand why some folks will refuse to eat buffalo. I have to assume they've just never tried it. Now I do sure enough, dearly love regular beef. Eat it all the time! Heck yes, all you beef producers out there! "It's what's for dinner"... But here's the deal: you can give me a chunk of buffalo whenever you please- and I gar-rone-tee, I will be one happy, happy guy. For my two cents worth, it tastes like the very best quality beef you ever put in your mouth.

The meat it self is not that hard to get your hands on. Any good butcher shop should be able to fix you right up. Shoot, even Kroger will have ground buffalo from time to time. Ask around. You can get it if you try. Take a hunk of that stuff out with you on one of your primitive, 18th century scouts... and you're doing exactly what so many of our kind were doing back 250/260 years ago. It's like you brought along some sort of original, pre-rev war, flintlock rifle or a cool old, antique tomahawk. Yet another integral and fascinating part to the puzzle. Come dinner time out there on the trail and you're cooking up your buffalo... Doesn't really matter if you're huddled up in some wild, forsaken rockhouse on the Little Barren River or com-fortably seated in a fine Williamsburg tavern on Duke of Gloucester St. with a bottle of good Madera and a choice array of elegant side dishes -you gotta love that buffler.

References

1. Boone, Nathan, My Father, Daniel Boone, Edited by Neal

O. Hammon, pps. 30, 31.

2. Trabue, Daniel, Westward Into Kentucky, Narrative of Daniel Trabue, pps. 58, 59.

3. Draper, L.C., Life of Boone, edited by T.F. Belue, p.256.

4. Trabue, Daniel, Westward Into Kentucky, Narrative of Daniel Trabue, pps. 73, 74.

The Lost Brigade Revisited | Muzzle Blasts Archives

Seems as though every single thing on God’s green earth possesses a subtle, inescapable, somewhat droll sense of humor. Even the basic, rudimentary forces of nature herself have a way of laughing/poking fun at you when you least imagine or expect it... And if a lad (or in this case, several lads) be smart, they’ll learn to laugh right along with Ma Nature and/or everybody else.

Making and Remodeling Muzzle Loading Pistols Part 3

The Historic Wolf Hills | John Curry | Muzzle Blasts Archives

“I first set foot in this Green River country in the spring of 1769. Jim Knox, from the Wolf Hills on the Holston, led a party of us into Kentucky to hunt. Folks called us the Long Hunters because we stayed gone such a time. The country was wilderness in those days. But few white men had ever seen it, and none had settled here.”

So begins an unassuming little book called “The Kentuckians”. The great Janice Holt Giles’ epic tale of a young longhunter’s amazing experiences during the late 1760’s in that vast, totally uninhabited expanse known as “the dark and bloody ground”. Lazy High School student that I was, I chose to read The Kentuckians under odious decree of a compulsory, English class, book report. Drat! My selection of this thoroughly astounding tome, owing mainly to its diminutive and insignificant size. Little did I know… Talk about lightning in a bottle! Hah! Right then and there began my irrepressible zeal for the saga of the longhunter which still holds me in its burly grip yet today.

Once anyone becomes seriously entangled amidst the bona fide history of true, classic longhunting; various intriguing references and allusions to this place called “the Wolf Hills” begin to pop up regularly. Arising from the most inauspicious, trifling parties you seldom ever hear about to the best known and most famous woodsmen of that age: “…Daniel Boone, accompanied by several hunters, visited the Holston and camped the first night in what is now known as Taylor’s Valley. On the succeeding day, they hunted down the South Fork of Holston river and traveled thence to what was known as the Wolf Hills, where they encamped the second night near where Black’s Fort was afterwards built. It is interesting to note at this point that Daniel Boone and his companions, immediately after nightfall, were troubled by the appearance of great numbers of wolves, which assailed their dogs with such fury that it was with great difficulty that the hunters succeeded in repelling their attacks and saving the lives of their dogs, a number of which were killed or badly crippled by the wolves. The wolves had their home in the cave that underlies the town of Abingdon. The entrance to this cave is upon the lot now occupied by the residence of Mr. James L. White.” 2 Yes… Actually, the huge entrance to the infamous Wolf Cave of so much extraordinary, longhunting lore, is now wholly contained within the backyard of a beautiful, Victorian house - located in central, downtown Abingdon!

For no more than were involved in this precarious, wild and woolly vocation; the Wolf Hills became a rather well known,

far-western landmark of its time. A sort of gathering point if you will, for longhunters headed west. Practically speaking, the stalwart pre-Revolutionary War era frontiersmen who took part in these lengthy, deepwoods ventures would in fact originate from all over the southern

and mid-Atlantic colonies. Renowned longhunting leader, Isaac Lindsay was from the

tiny settlement of Newbury in western South Carolina while his older brother, Thomas Lindsay lived in Pennsylvania. The illustrious James Harrod (an important longhunter in his own right) hailed from southern Pennsylvania as well. James Knox and Henry Skaggs were both from Virginia whereas the previously mentioned, larger-than-life, Daniel Boone owned a farm in the Yadkin Valley of North Carolina. Usually rallying… joining forces under the guidance and direction of one or two experienced, highly competent men who would serve as a Captain of sorts. (And by the term “Captain”, I use that in its most vague and innocuous connotation.) The Wolf Hills of southwestern Virginia served as something of a pre-appointed, “meeting up” place where groups of professional hunters bound for the fabled, Can-tu-kee would assemble and mobilize in preparation to their impending departure.

Having no specifically appointed date, some might get there many days in advance, setting up their camp and waiting for their friends. Some might arrive shortly before - some arriving just in time to head out – with others not infrequently arriving a tad late and having

to track the company down just to catch up. The most common collection period being late spring, like May

or June, however companies of longhunters could find themselves encamped and lingering at the Wolf Hills in any month, during any season. . A general, basic date would be communicated amongst everyone connected with a particular longhunt, to present themselves there at the Wolf Hills with all the intended participants made aware of it. Typically, a comfortable amount of time would be allowed for each man to fully arm and equip himself, in addition to furnishing all the necessaries. This might encompass two or three pack horses plus his own mount, tack, powder, bar lead, trail gear, salt, a blanket or two, along with anything else he might think of: i.e. mittens, a mending box, spare flints, fishing kit, basic blacksmithing tools, etc. These obligatory essentials together with enough jerk, parched corn, coffee and sugar as he might see fit… At least enough to last until he finds himself surrounded by the unbroken forest and is able to hunt for victuals with his trusty firelock.

All this acquired, organized, packed up - and he’s ready to head out. Now repeated selection and usage of the Wolf Hills vicinity didn’t just happen by accident. All these groups of highly experienced woodsmen weren’t just stomping around in the wilderness and suddenly decided “hey, let’s set us up a camp and wait for everbody right here”. No, no. Merely arriving at this crucial place meant you’d already done your homework, received an invite, knew what you were doing and you had some pretty big plans. The Wolf Hills (as a point of embarkation) was in fact, quite strategically located upon what had been recognized from

pre-Colombian times as the old, Warriors Path. A main artery penetrating into the uncharted, unknown, colonial far-west with its major branches extending all the way out to the Mississippi as well as northward into the eastern Great Lakes. This thought-provoking moniker was in due course changed and the ancient trail itself significantly modified during the longhunting era to become “The Hunters’ Trace”. An untrustworthy, bewildering passageway beginning in earnest from Staunton, Virginia; drifting through Cumberland Gap and ultimately reaching its western terminus way out in modern-day, south-central Kentucky and further on into the French Lick region of Middle Tennessee.

Once through Cumberland Gap the tremendous amounts of game became incredible. Moving from one area to another in four week to six month intervals; semi-permanent, working/living sites better known as “station camps”; centrally established within game-rich hotspots possessing curious names like Wasioto Pass, Stinking Creek, Raccoon Springs, Skin House Branch, Knob Licks, Big South Fork and the Barrens would serve as these longhunters’ various and sundry, homes-away-from-home… Any given company sustaining this rootless, nomadic lifestyle most often for a grand total of anywhere from one to two and a half years. Common procedure was for hunters to radiate out from those temporary station camps in all directions – north, south, east and west. Either by themselves or in little groups of two or three for a period of roughly, ten days to nearly three weeks. Due to the sheer numbers of hides and furs, game would be skinned on site and brought back to the station camp for half-dressing, then stored away in large hide houses to await their eventual transportation back over the mountains to the trading posts. This comprised the everyday business of the longhunter: Roam the Hunters’ Trace into the west. Establish station camps here and there. Kill/process game. Take it all back east - and reap your new-found wealth. Notwithstanding… Right here, in the Wolf Hills of Virginia. Just a stone’s throw east of Moccasin Gap - is where the game was initially set in motion.

A fleeting handful of years and the grand adventures passed on by with southwestern Virginia becoming increasingly more populated... By degrees, more civilized and conspicuously developed. Homesteads, towns, stockades springing up here and there. The days of an unsettled, wild and unbroken Virginia frontier were slowly turning into timeworn, half-forgotten memories. Our youthful, vibrant nation had determined to improve and cultivate the west. Longhunting was on the wane and a different kind of frontier was emerging: “Soon after the arrival of Mr. Robertson on the Watauga (1772)… it became settled from the Wolf Hills, where Abingdon, in Virginia, now is, to Carter’s Valley.” 3 Alas (as with everything else in the course of history) the Wolf Hills, longhunting and indeed, the longhunter himself shortly thereafter, slipped away; almost imperceptibly fading off into obscurity. But not the wolf! Distinguished Revolutionary War era, Virginia/Kentucky frontiersman, William Clinkenbeard laments: “The wolves used to come and take the pigs and things close up around the Station...”4 (I’ll bet they did.) Virginia would be a while yet shaking off her wolf population. Not unlike the vanishing longhunter during his brief heyday… hunting was in their blood. They knew nothing else. If the situation wasn’t working where they were, if problems developed, if the game played out – they’d simply adjust or otherwise drift off entirely, to another “canine” station camp.

The Wolf Hills might be lost… a thing of the past but this to the wolves was only a minor, inconsequential setback. The wolves would never yield. They weren’t created to yield. In the midst of unendurably hard times, they merely repositioned themselves; while simultaneously adapting and redefining their tactics for survival with regard to these strange, dangerous, highly sophisticated, human predators. Avoid them when they had to; eat them when they could… Food is where you find it ya know – either at home or on the trail.

Traveling westward into Kentucky with his family and a small group of settlers, late eighteenth century pioneer John Hedge tells us: “Wolves came around the wagons again. They were mighty bad in them days in Kentucky, on young cattle, horses and calves.”5 Cattle and horses, huh? Consider yourselves lucky! Guess they figured if the loathsome humans drove them off, at least they could supply ‘em with a cow or a horse every now and then… Got to do what ya got ta do, right? And pretty much nobody cares about the wolves but the wolves.

Well… Wolves are long gone now. From around these parts anyways. Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, Kentucky and all through the Ohio Valley. Just like the longhunter - gone. You gotta admit though, they put up

a darned good fight. Word is they still have a few wolves way out in the modern-day west. A very few… But from what I hear, most people out there (farmers, ranchers and such) don’t particularly like ‘em and their days (similar to their eighteenth century cousins), sound ominously numbered. Being a carefree rambler, a roving, habitual wanderer and an unapologetic hunter myself, I’ve always sort of identified with wolves. My path through the

forest is my own. Imperfect, unexceptional no doubt, but mine nonetheless. I chase my tail, howl at the moon and drift with the wind, as my instincts decree. Yet my hunting grounds dwindle and in many places I’m no longer welcome. That wild, uninhibited, wide-open deepwoods lifestyle I’ve grown to love is increasingly becoming harder and harder to attain. Reputable, historically legitimate longhunters of today are hard pressed as well, to find even the ever-

receding scraps of it. Still we continue to roam, prowl, dream, hope against hope; hunt where/when we can. And then we move on... Sometimes I think, in my last life – I was born a wolf.

John Curry

References:

1 Giles, Janice Holt, The Kentuckians, p. 2.

2 Summers, Lewis Preston, Southwest Virginia, 1746- 1786, p.76.

3 Haywood, John, Civil and Political History of the State of Tennessee, p. 55.

4 John D. Shane’s interview with William Clinkenbeard, Filson Club Quarterly, Vol. 2, No. 3, April 1928, p.105.

5 John D. Shane’s interview with John Hedge, Filson Club Quarterly, Vol. 14, No. 3, July 1940, p.181.

Making and Remodeling Muzzle Loading Pistols Part 2

1 of 1000 Endowment Program Update

Visit www.nmlra.org/1of1000 to learn more about the 1 of 1000 Endowment Program or to download either of the above items.

Preserving the "Journal of Historical Armsmaking Technology" Book Series

Over the Falls by John Curry | Muzzle Blasts Archives April 2020

Making and Remodeling Muzzle Loading Pistols Part 1

Making muzzleloading pistols is a much-maligned craft. “To a gunsmith, Kentucky pistols leave a lot to be desired. Pistol making is time-consuming and challenges all of the skills required to make a good rifle. A barrel, breech plug, and lock have to be inletted. Triggers, thimbles, nose cap, butt cap, side plate, bolts, screws, sights, ramrod, and stock all have to be created just as they must for a longrifle. To be of use, the hardware has to be of rifle quality.

ADA Rifle Project Giveaway Update

Indiana Gunmakers and Their Muzzle-Loading Longrifles 1778-1900

The high-quality book is hardbound and 324 pages of heavy, 100# coated paper with a matte finish.

It contains biographies of nearly 1,000 gunmakers that worked within the boundaries of present-day Indiana between 1778 and 1900 as well as nearly 800 high resolution photographs of their muzzle-loading longrifles.

The book organizes the gunmakers alphabetically and also by county for easy reference. A section on gunmaker migration includes six color maps that depict county organization and state growth between 1817 and 1840. Statistical tables show what state and/or country the gunmakers were born.

It is printed in full color and authored by veteran student of the longrifle, Jeffrey J. Jaeger.

The Bevel Brothers RELOAD : Grass Wads | Muzzle Blasts Archives

Written by The Bevel Brothers

Bevel Up: Back about 20 years ago we wrote an article about hunting loads for smoothbore muzzleloaders. The question had to do with the best loads for small game using shot and deer using patched round ball. One of our “recommended” loads for shot included the use of field expedients such as grass or corn shucks as over powder and overshot wads.

Bevel Down: That brought in some hate mail from a few naysayers who contended that the use of anything other than a commercial card and fiber wads in a shotgun was dangerous. The alleged danger was supposed to come from the wadded up grass or leaves or corn shucks some-how turning into a barrel obstruction and causing the whole thing to blow up in our collective faces.

Eventually, we were able to rally enough experts on the subject to say that there was and is no such danger. But even though we were eventually vindicated, there is still a persistent belief that only properly sized and perfectly cut card and fiber wads (or patched round ball) should be used in smoothbore muzzleloaders. Back when we were interested in doing things in a “period correct” way so as to know what it was like to hunt the way the old-timers did, we used leaves and corn shucks in our shotguns out in the woods all the time. We still do it sometimes if we forget to bring the right cut wads when we leave the house. It’s not the best wad material, but if the choice is shooting with less than perfect wads versus not shooting, we always pick the alternative that keeps us in the woods and shooting.

Bevel Up: I have to admit that I do most of the smoothbore/shotgun shooting in this family. I’m finding that as my eyes age up over the 70-year mark, the sights on my Tennessee squirrel rifle are getting harder and harder to see. My favorite muzzleloaders for squirrels and rabbits these days are a 20 gauge flintlock trade gun, an old original Bannerman conversion 1863 Springfield musket cut down and bored out to a 17 gauge smoothbore, and an old Damascus-barreled percussion English double that has one barrel bored 15 gauge and the other 13 gauge. I like that double because I can put a little bit heavier load in the bigger barrel for a little bit more range if I need it.

All of those guns take a different sized wad and I’ve got commercially made wads for all of them. You can get good commercial wads in just about any size you need from Circle Fly (online at Circlefly.com) or from Mike Eder (at his booth on Commercial Row at Friendship or at his shop at 6929 Beech Tree Rd., Nineveh, IN 46287).

But there are times when I just grab the wrong bag on the way out the door, or forget to re-stock my wad sup-ply in the right bag, or I sometimes get to fooling around shooting at dirt clods or wasp nests and just plain run out.

That’s when I look around for something else I can use for wads. Usually, that’s grass or weeds like foxtail grow-ing up in a ditch or next to the fence, or some leaves if they’re not too dried up and crumbly.

Bevel Down: We always knew that a wadded up handful of grass wouldn’t produce as good a gas seal in front of the powder, and would probably get tangled up with some of the shot pellets and thin out the pattern. So we didn’t expect to get the performance out of grass and leaves that good precision cut card wads would give.

But we had never actually tested them against each other. So big brother grabbed an old 11 gauge Belgian double barrel of his and we headed to the Bevel Brothers Scientific Range Lab up at Wiseacres (my farm).

Bevel Up: We set up the Oehler 33 chronograph and cast about for some suitable “field expedient” wad material, which turned out to be some old damp foxtail grass grow-ing next to the range. I loaded up a more or less standard charge for that shotgun (90 grains of 2fg GOEX with

an ounce and an eighth of shot) using the regular card and cushion wads in one barrel and the grass in the other. The other barrel got the grass over powder wad which was a gob about two and a half inches long and somewhat bigger around than the bore diameter so that it would be good and tight when I crammed it into the barrel. I pounded the ramrod down on the grass several times so as to get it good and tight and compacted over the powder. After that, I poured in the shot charge and used a thinner bit of grass folded up so as to be about a quarter-inch thick for an overshot wad to hold everything in place. I have to admit that we were surprised at the chronograph results. Even though we expected the grass to lose some velocity, it turned out to be much more of a loss than we anticipated. The shots using regular card and cushion wads averaged 1050 feet per second at about 10 feet in front of the muzzle (what the experts call an instrumental muzzle velocity because it isn’t actually measuring the speed of the shot right at the muzzle). But the shots using grass wads averaged only 650 feet per second – about 40 percent less than with card wads! Patterns at 20 yards were a little bit thinner with the grass wads, too. Not so bad that you couldn’t kill a squirrel or a rabbit with it, but there was always a noticeably thinner area in the middle of the pattern, and the center of the pattern seemed to be about four to six inches lower with the grass wads.

Bevel Down: So then I got to thinking that maybe grass was just too spindly and loose to make a good wad. May-be leaves, being more like sheets of paper would sort of fold or mat up into a better gas sealer than the grass wads.

So I picked up a bunch of oak and maple leaves from last fall and sort of worked them into a ball like you would roll a ball out of clay or cheese or cookie dough. We tried a few shots with those over the chronograph and found that they shot on average about 100 feet per second faster than the grass wads. So the leaves made a little bit better over powder wad than the grass, but the patterns using folded up leaves for the overshot wad tended to have a more pronounced donut hole in the middle than the grass over powder wad did. That’s probably because it was hard to make an effective overshot wad out of the leaves without using quite a lot of them, which made the top wad almost as big and heavy as the bottom (over powder) wad. The lesson there is if you have to shoot this way use a ball of leaves over the powder and some folded up grass over the shot.

We also noticed that fouling from all of these grass and leaf loads was much worse than with the card wads. We suspect that is mostly due to the lack of compression giving a less than complete burn of the powder charge, but the lack of a tight-fitting card wad and lubricated cushion wad to scrape the crud off the bore every shot might also have something to do with it.

Leaves seem to make a slightly better over powder wad than grass.

Felt recoil with both types of loads seemed to be pretty close to the same, with the leaf load maybe generating

a little less recoil than the grass, but both pretty close to what the card wads produced. That was a puzzlement until we got home and weighed some of the wads. Turned out that the old (slightly damp) grass wads weighed on av-erage about 130 grains and the leaves weighed around 110 grains. That amounts to adding about the equivalent of an extra quarter ounce or so of shot to the total charge weight of a regular card wad load, which would account for that extra recoil even with lower velocities.

The calculated free recoil energy of the grass and leaf loads was about 36 to 38 foot pounds while the card wad load at the much higher velocity was about 41 foot pounds.

Bevel Up: So what did we learn from that experiment? First off, yes, you can use wadded up grass and leaves for wadding in a smoothbore. The problem is that your patterns are going to be thinner and you’ll lose close to half the pellet velocity and energy, which will drastically reduce the effectiveness of your shot. The retained pellet energy using the grass wad is about the same at 20 yards as a charge of shot using a card wad at 40 yards. It’s a little better for the leaf wad load, but not much. And with just a wad of grass holding the shot charge in place you’re also likely to lose that load of shot once in a while if you’re not real careful about not jostling the gun around too much chasing up and down hollers after little furry beasts.

So unless you are just absolutely left with no other solution, you need to use real card wads and real cushion wads if you are going to get optimum results with shot out of your smoothbore. You’ll get far more power, less fouling, and better patterns with regular card wads.

And by the way, we don’t recommend using plastic shotgun wads. Plastic wads are banned from use at the Friendship shotgun ranges. That’s because black powder burns at a higher temperature than smokeless powder and will partially melt regular one-piece plastic wads. That little bit of melted plastic then tends to leave bits of itself in the bore that can build up and then smolder and ignite the next powder charge you pour down the barrel. I’ve tried using plastic wads and AA hulls with black powder in a breech loading shotgun and found that it not only melts the wads, but also the plastic shotgun shells. That melted plastic and black powder fouling gunk made a mess that was exceptionally difficult to clean out, too. And besides, it just isn’t natural -- using plastic in a muzzleloader, that is. So that’s why now I only use paper shells and card wads to reload black powder ammo for my old Damascus double – just like they did in the old days.

There are some advantages to using a shot cup like those plastic wads have, though, so one of our upcoming research experiments will look at making and using paper shot cups to improve shot patterns.

Wyatt Frist “Never Give Up” Fundraiser

In March of 2021 Wyatt was in a severe traffic accident and ended up with multiple surgeries and a lengthy hospital stay. Wyatt is home now and continuing in his long road to complete recovery.

Come join us for 2 raffles, a silent auction and GoFundMe to raise money for Wyatt!

Join us from September 11-18, 2021, at the NMLRA Trap Range for a silent auction and raffle for some great prizes and on Wednesday, a special Calcutta shoot at 6PM.

Raffle #1 is for a custom-built muzzleloading pistol, a shooting box and a powder horn. Tickets are $10 each.

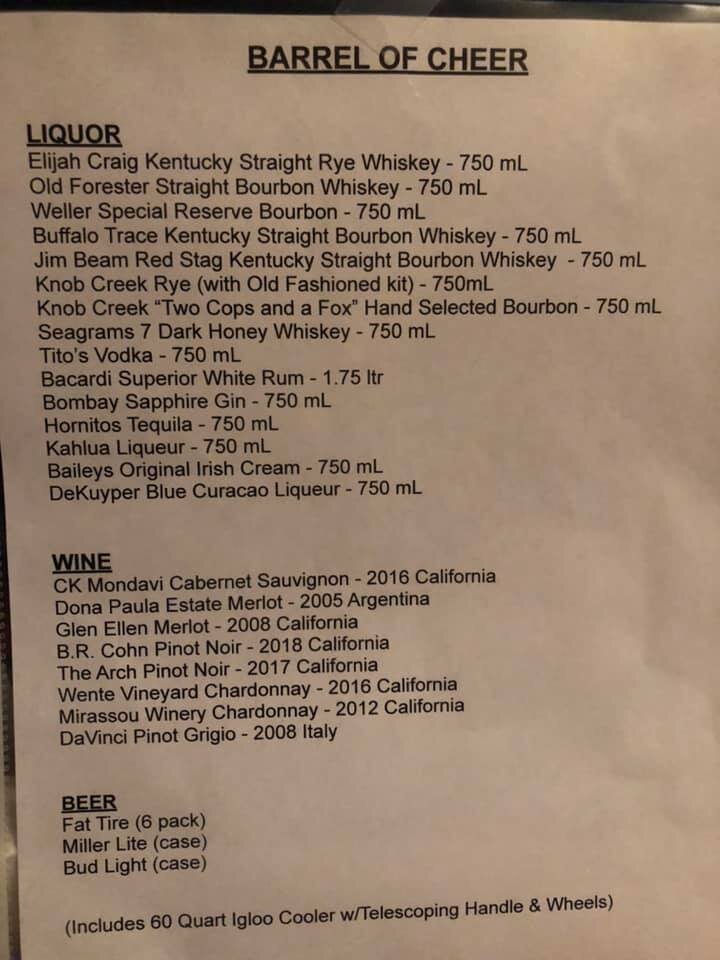

Raffle #2 is for a “Barrel of Cheer”- an assortment of bottles of liquor, wine and beer! Tickets are $5 each or 6 for $25.

If you can’t join us those dates but would like tickets, please contact Amanda Weisel or Keith Fox. We take cash, check, PayPal or Venmo. Proceeds from these and the GoFundMe page go to Wyatt and his #1 caretaker and father, Robert Frist, for costs associated with the accident.

If you can’t make it in person, no worries! We have a GoFundMe page if you’d like to donate and share. Follow the link below for the GoFundMe:

You do not need to be present to win prizes from raffle or silent auction. To buy tickets for raffle, join us in person September 11-18 at the trap range of the Walter Cline Range of the NMLRA, contact Amanda Weisel or Keith Fox directly or email ngunmlra@yahoo.com to purchase.

Silent auction is an in-person event only. No online bids. Do not need to be present to win. Silent auction items will be listed here as they come in, so keep checking for updates on auction items.

Silent Auction items include:

• Framed shotgun shell American Flag

• “Homemade” Gift Basket. Assorted homemade goods made and donated by Johnny Fern and Paul Anhofer

• $50 Gift Card from Hunt to Eat

• Workout package from Amanda Valentine and Cincy 360 Fitness

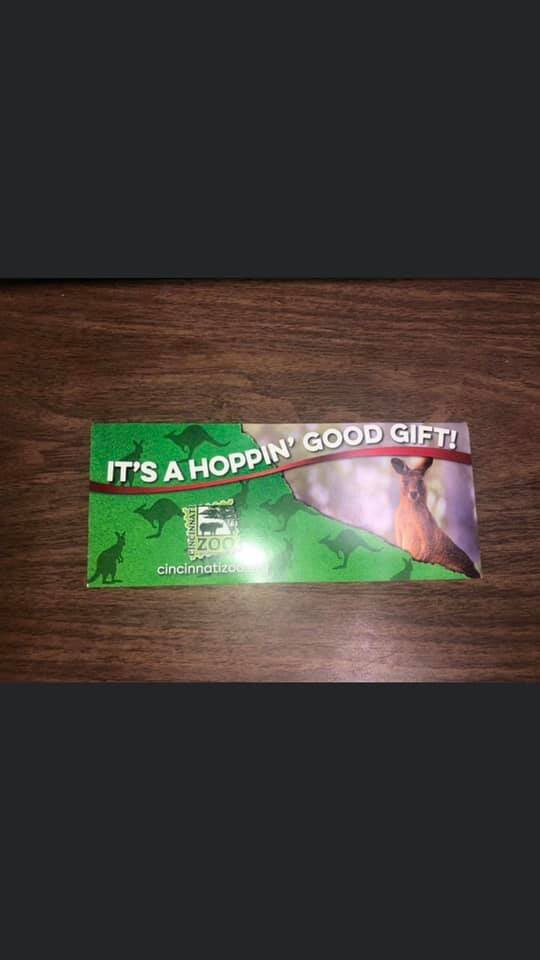

• Cincinnati Zoo Membership

• Elephant Painting

• Milwaukee Hammer Drill/Driver Kit

• Corona Flashing Bar Sign

• Bumpboxx Ultra Bluetooth Speaker

• Hand painted canvas of Wyatt shooting

• 1 Night Stay at Karen Laine’s (HGTV star) AirBNB in Indianapolis, IN

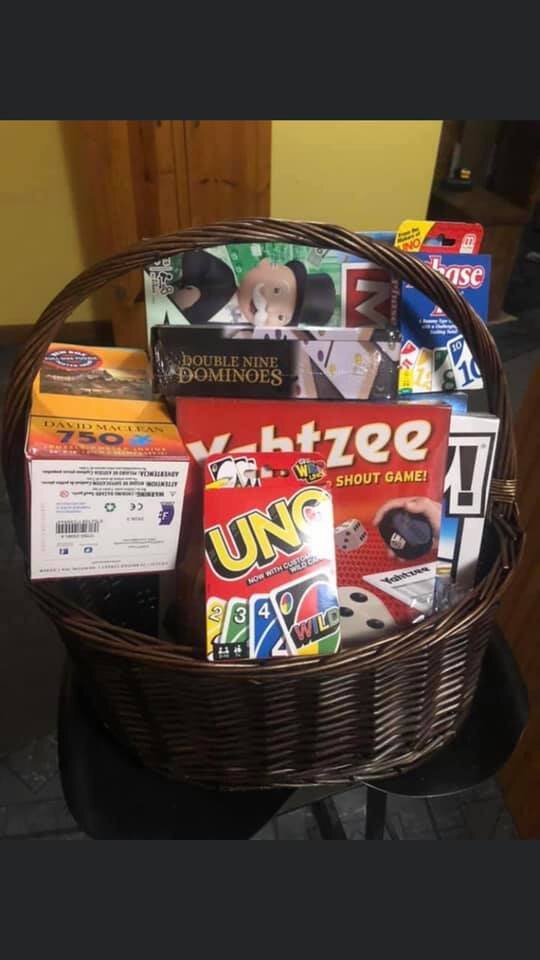

• “Game Night” Gift Basket

• Pastured Pork Bundle from Whispering Willows Farm (not available till November)

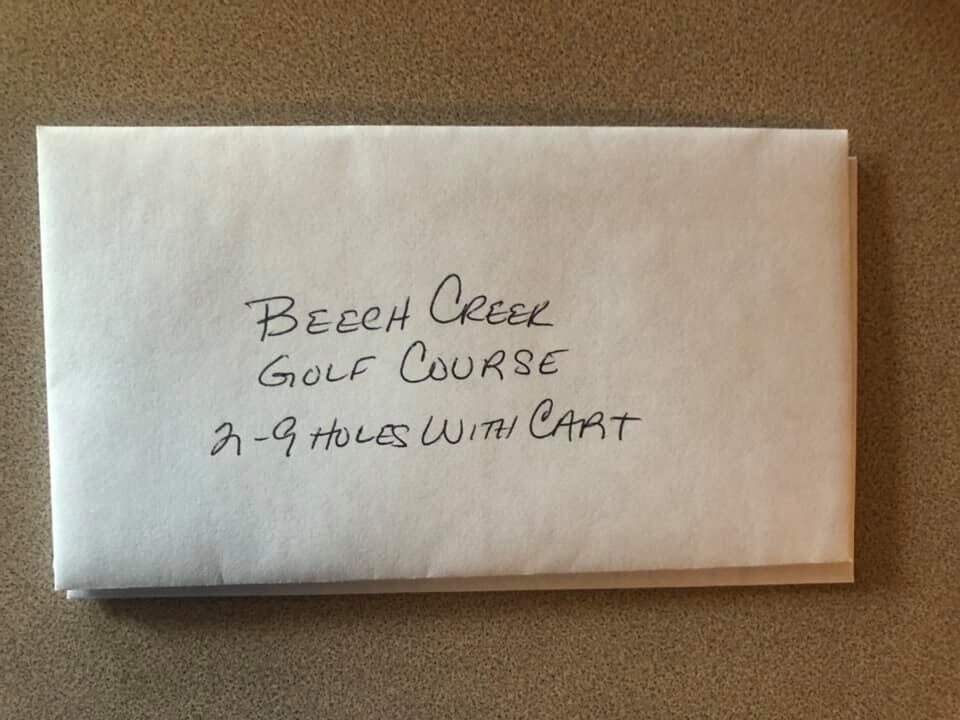

• (2) 18 Holes with Cart at Beech Creek Golf Course in Cincinnati

• Coffee basket

• 20x30 Framed Sunflower Photo donated by Bec's Photography!

• 2 T-shirt’s, hat and drawstring bag from Queen City Revolt

• (2) GCI Outdoor Rocking camp chairs!

•Leather shooting bag made and donated by Daniel Boehringer

•Leather shooting bag made and donated by Jeff Po-boy Luke.

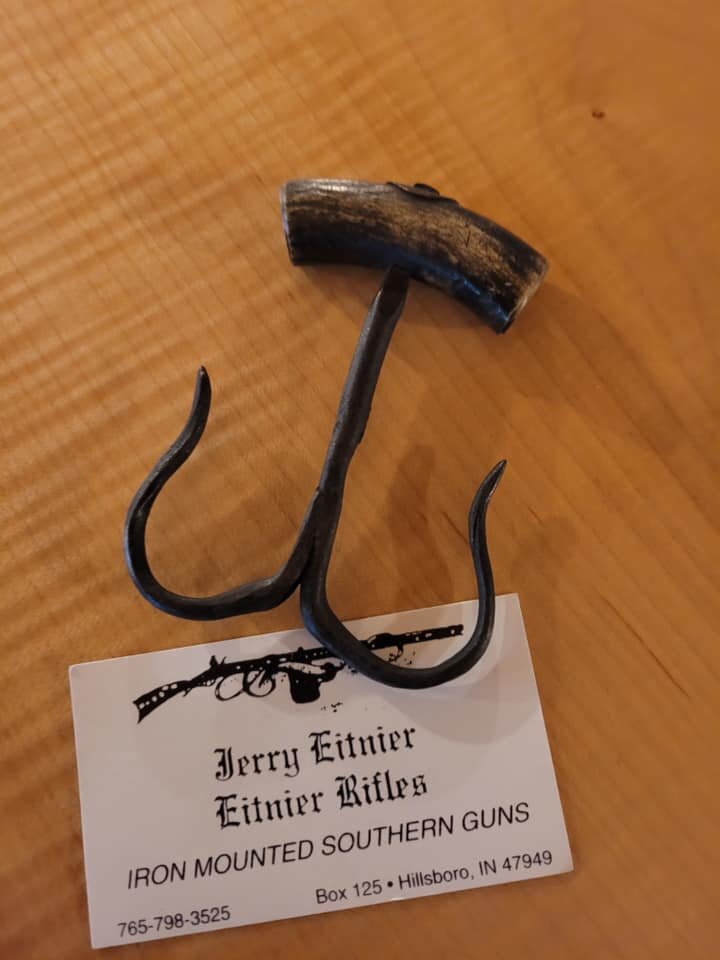

•Game hook made and donated by Jerry Eitnier.

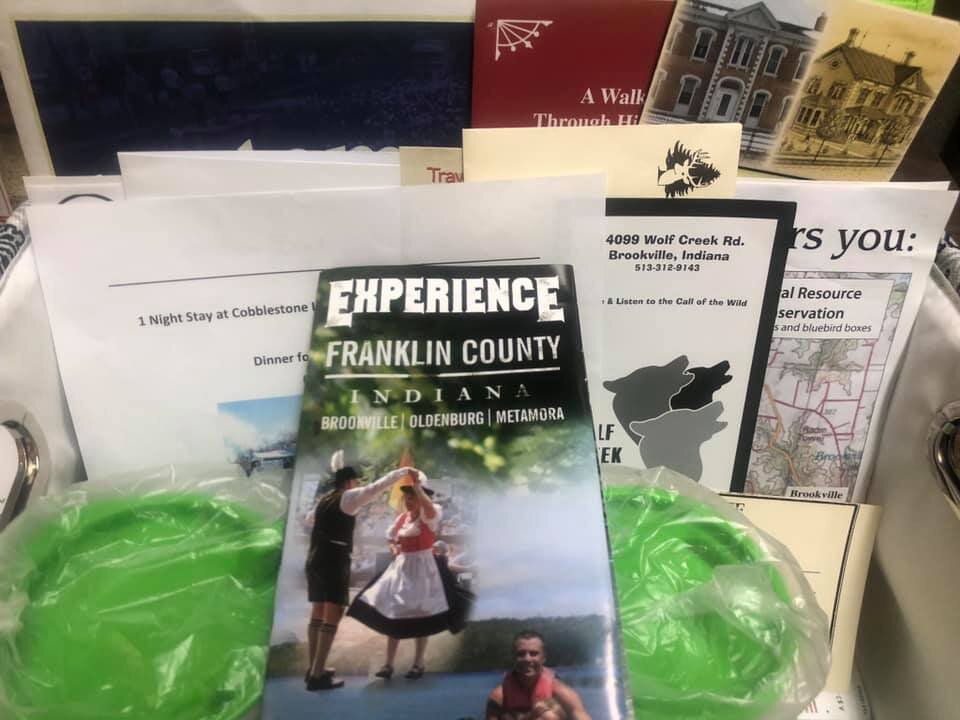

• “Experience Franklin County” Basket

•Pastured Poultry Bundle from Good Shepherd Farm

•Penguin Painting

•Meat Bundle from Flourish and Roam Farm

• Goat Soap Bundle from OFP Farm

•Apothecary Gift Basket from Barefoot Hippie Homestead

•Fiona the Hippo Kiss Print

•Fishing Lures made and donated by Jon Evans

•Large Yarn Knitted Blanket made and donated by Linda Schrimsher

•Spice Collection from Reload Rub and Seasoning